At our May meeting, Peter Tea reintroduced us to two trident maples he had worked on in previous sessions. He did some more work on one of them, then moved to a Seiju elm and proceeded to give it some severe, but highly educational, pruning.

Peter made it clear at the outset that he didn’t want to do too much writing on the board this time, but rather wanted to do a lot of work on the trees. But he did list some of the most relevant review points for us to bear in mind as we watched him work. He listed the techniques most appropriate for tridents and elms at this time of year: pinching, defoliation (not for elms), cutting, and wiring. He also wrote down the two conflicting goals when we must decide whether or not to make a cut: thickening versus division. Finally, he listed the things we can manipulate to control our trees’ rate of growth: sun, water, soil/pot, repot interval, fertilizer, and cutting. His focus that evening was on cutting and wiring, with an emphasis on how those techniques can help us expose different parts of our trees to sun.

The first tree Peter worked on was a trident maple we have seen before, when he drastically cut it back at his previous demonstration. It was very instructive to see how it had changed, largely in line with Peter’s original intentions. He had dramatically chopped back the top of the tree so that the lower branches would receive more sun and grow more strongly. He pointed out that since the last demonstration he had continued to cut back the top of the tree, to encourage division, while he let the lower branches grow into long runners so that they would thicken close to the trunk.

This was the first of many times this evening that he emphasized how important it is with trees like trident maples and elms to chop away everything above if you want to develop a branch lower on the tree. This doesn’t necessarily mean that you have to chop the top of the tree off or severely back, but the branches up there must at least be shorter than the one(s) you’re trying to develop. Peter was still unsure whether or not he will eventually want to keep the top of this trident, but as long as he continues to cut and defoliate it, he doesn’t have to make the decision right away.

An important point Peter made with regard to wiring trident maple and other deciduous-type branches: don’t aim for a juniper-like pad when developing small groups of young branches. Rather than spreading branch clusters horizontally to create a single-level fan, you should be randomizing the vertical elevation of such branch clusters to give a look something like a sideways broom. In this way, you will create a more natural overall silhouette for the tree that matches its species, rather than a multilevel system of pads, which is fine for junipers and other conifers, but looks unnatural on deciduous trees.

Wrapping up on the first trident maple, Peter gave us an interesting example of how much the growth rate of a tree affects your styling decisions for it. He showed us a lower runner that had successfully fattened a little, but its first internode was too long for the overall design. Stylistically, it needs to be removed with the hope that one or more of the small shoots popping up around its base might replace it. But armed with the knowledge of strong trident maple growth habits, particularly in late Spring, and what we’ve learned about balancing a tree’s energy, we can be reasonably certain that immediately removing that runner at its base will not have the desired effect. At the very least, the new shoots left at the base will receive the energy that used to be going to the runner and will suddenly grow faster, once again creating leaf internodes that are too long. Even more likely, the runner’s stump will resprout.

The solution is to remove the original runner slowly. Begin by cutting past the first leaf node. The branch will survive and probably divide, but will draw less energy than it did before. This will keep the transfer of growth rate to nearby branches at a manageable level. You may even want to cut the resulting divided tips later, to delay cutting the runner and giving the new branches more time to slowly take over. Once you are satisfied with the promise of one or more new branches, then you cut off the original runner at the base. Remember: slower growth will allow more refinement, with shorter internodes and better, more slender eventual tapering.

Moving on to the other trident maple, Peter focused on one area that was looking particularly odd. One shoot near the lower middle of the tree had grown much more rapidly than surrounding areas and was creating a reverse taper that could be recognized as undesirable by anyone with even minimal aesthetic sensibility. To confirm our suspicions, Peter pointed out that a branch should never be more than 30-50% the size of the spot where it grows off the trunk. The old growth of this branch, close to the trunk, was well below this thickness, but the new growth further out was exceeding it, causing the reverse taper.

The first reaction might be to cut off the out-of-control new growth and try again, but this may not work, and repeated attempts will cause adverse results, like creating a bulbous knuckle from repeated new shoots. Peter says, “Be patient!” because the branch will eventually thicken near the base. This is because the new growth must get to the size of the old growth, or even larger, before the old growth will fatten. Sure you’re going to have a giant, long runner that looks out-of-place for a while, but once it’s large enough, the part close to the trunk will fatten, and then you can proceed to cut the new growth where it is stylistically desirable and you won’t lose a year or more of growth by having started over.

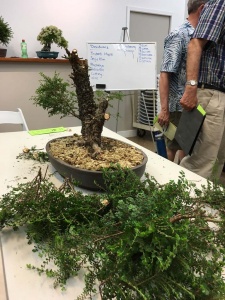

There was not as much time left for the Seiju elm as Peter had planned, but he quickly got to business and managed to remove a shocking amount of material in the short time he had left. He began by cutting off the entire top of the larger half of this double-trunked tree because it had too many big branches and small branches at the bottom needed encouragement. Then he chopped off two major branches on the smaller trunk. The first branch was too long with no taper, and the other was above the first and needed to be removed in order to encourage the shoots that would inevitably spring up where the first branch was cut.

RSVP for an upcoming workshop and receive guidance in applying these techniques to your trees!

– David Eichhorn